The Week in Alt Fuels: The fuel fog

LBM is a case study that shows why IMO must clarify the unknowns soon.

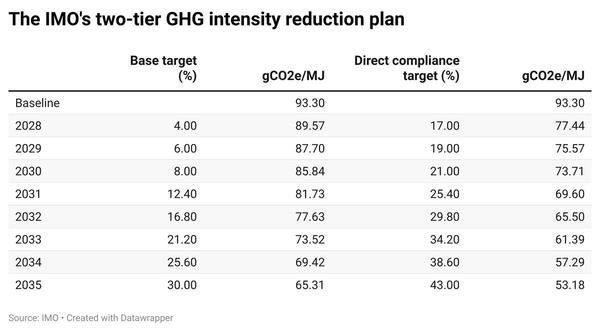

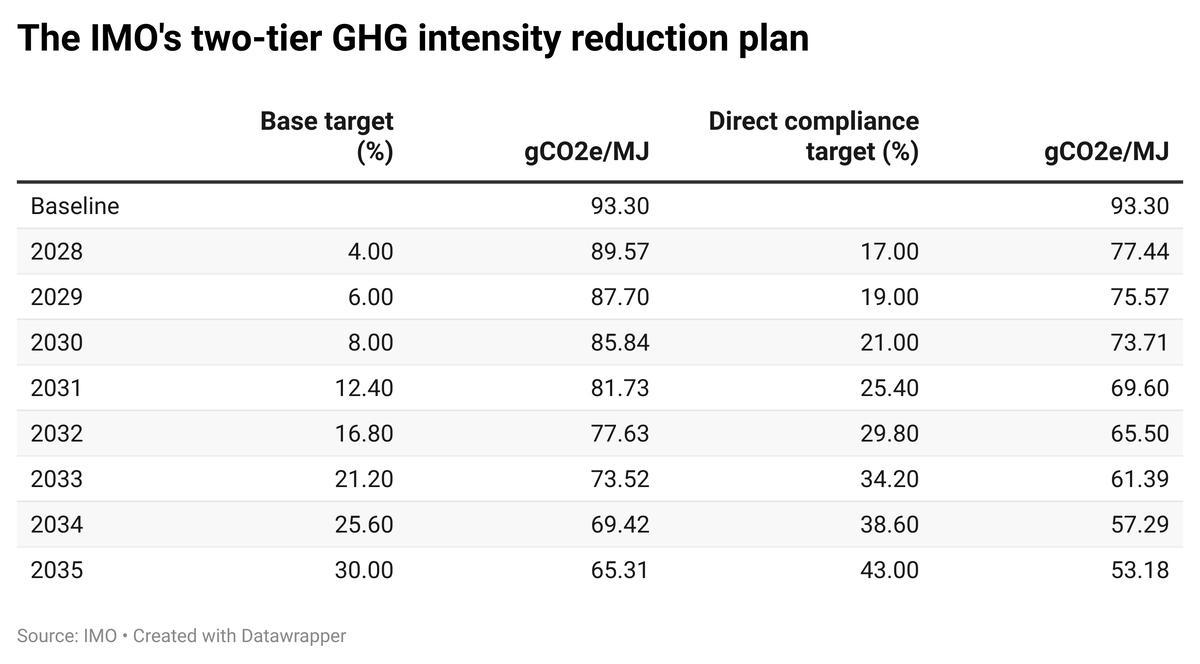

TABLE: Annual GHG fuel intensity reduction targets for base and direct compliance, relative to GFI reference values. IMO, ENGINE

TABLE: Annual GHG fuel intensity reduction targets for base and direct compliance, relative to GFI reference values. IMO, ENGINE

Liquefied biomethane (LBM) has emerged as one of the strongest compliance fuels in Europe, with recent bunkering activity testament to its rising popularity in the region.

Its climate credentials are impressive.

FuelEU Maritime default emission factors show that LBM's well-to-wake (WtW) GHG intensity ranges from 15.54 gCO2e/MJ for diesel slow-speed engines to 28.43 gCO2e/MJ for Otto medium-speed ones.

Real LBM well-to-tank (WtT) GHG intensities seen in the market vary widely, from as low as -80 gCO2e/MJ to around 20 gCO2e/MJ. These will of course have huge implications for the WtW calculations.

But when we use default factors, LBM's WtW GHG intensity is far below FuelEU Maritime’s 2025 cap of 89.34 gCO2e/MJ and will remain well below the IMO’s base- and direct GHG intensity targets until at least 2035.

In Rotterdam, the economics also stack up.

Dutch-rebated LBM is priced at around $1,340/mt, a steep $642/mt premium over LNG. But adjusting for energy contents and layering it with EU ETS savings and FuelEU’s potential pooling values, the numbers shift dramatically.

ENGINE analysis shows that HBE-rebated, VLSFO-equivalent LBM in Rotterdam can generate pooling values of $500-600/mt for voyages between EU ports, depending on engine methane slip.

Combined with carbon factor of zero under the EU ETS, LBM’s real cost in Rotterdam can potentially drop to around $480-590/mt - making it the one of the lowest-cost compliance routes in the EU.

But we don’t know how Rotterdam’s playbook will pan out on a global scale.

For one, Dutch rebates are expected to be overhauled by 2026, with separate obligations for the marine, inland marine and road sectors. How these will interact with the IMO’s framework remains unclear.

Then there is the pooling element, which isn't included in the NZF draft. Instead, it introduces a surplus unit (SU) transfer system. Comparing it with FuelEU’s pooling mechanism is tempting, but imperfect.

Under FuelEU, vessels can transfer or sell compliance surpluses within a pool and the total balance is distributed across individual ships. The total pooled compliance must be positive for the pool to be valid and every individual vessel must not have a deficit after the total pooled compliance has been allocated.

On the other hand, the IMO’s approved draft includes “grants of surplus units [SUs] for over-performing vessels which can be transferred to other vessels to offset a deficit in the upper deficit tier, to incentivise the use of bio- and other renewable fuels,” explains Thomas Edelgaard Christensen, maritime lawyer and managing counsel at Gorrissen Federspiel.

That flexibility creates new opportunities, Christensen argues.

“SUs can, however, be transferred (and priced) wholly or partly to different vessels without the requirement for these vessels to be pooled as a whole. It will thus likely be a more flexible and manageable system than the FuelEU pooling,” he adds.

But the economics of these transfers, including the rough price floor for these SUs, remains unknown. And whether this will benefit LBM after 2028 or not, depends on the pricing of surplus units and fuel lifecycle assessments.

The biofuel elephant in the room

But lacking clarity around emission factors or feedstock eligibility adds more regulatory uncertainties.

For example, the IMO has not clarified whether it will exclude or cap use of crop-based biofuels.

In the EU, FuelEU does not allow crop-based biofuels to count as low-emission. In the EU’s RED III, there are limits on how much crop-based biofuel can count towards transport targets (and phases out high-indirect land use change oils). While this does not ban their use, it indirectly curbs incentives for crop-based marine biofuels.

There’s currently no such provision in the IMO, and climate advocate Transport & Environment has argued that this lack of clarity and tightening global regulatory targets “are likely to incentivise ships to rely on the most affordable crop-based first-generation biofuels on the market, such as those produced from vegetable oils, including palm oil, soybeans or rapeseed.”

These fuels are cheaper than the waste- and residue-based biofuels, but not sustainable due to their impact on land use and the environment. And by the time the IMO’s framework is expected to take effect in 2028, feedstock eligibility, availability and costs will all look different from today, making it a headache to model prices.

A harder global race

Europe has shown how rebates, penalties and pooling can make LBM look competitive. But the global race will play out in a far tougher environment.

The real economics of this are near impossible to pin down today. The IMO’s framework won’t take effect until 2028, by which time fuel markets will look very different. Costs for LNG, biomethane, biofuels and synthetic fuels could all shift dramatically, making any price modelling speculative at best.

Will VLSFO-equivalent B100 biofuel still command a premium over VLSFO-equivalent LBM in Rotterdam and other ports, or will prices converge? Will IMO surplus units generate enough value for shipowners selling them to offset their green fuel premiums?

The short answer? We don’t know.

What we know is that LBM is building a stronger track record in Europe. But the unanswered questions around pricing, rebates, surplus unit transfers, emission factors and feedstock eligibility point to a larger reality: the IMO’s Net-Zero Framework is itself clouded by uncertainty.

And those uncertainties will shape not just LBM’s future, but the competitiveness of every alternative fuel.

In other news this week, DNV’s database recorded 14 new alternative-fuel capable vessel orders in September, marking a slight recovery after a dry August. LNG dominated September's orders with 12 new vessels and LPG accounted for the remaining two. No new orders were placed for methanol- or ammonia-capable ships.

Lloyd’s Register (LR) has partnered with US-based startup Deployable Energy to study the feasibility, safety and risk profile of deploying nuclear micro-reactors for ship propulsion. LR and Deployable Energy will now focus on safety and risk assessments, with a pilot project targeted before the end of this decade.

Energy firm Axpo has delivered 3,000 cbm (1,341 mt) of LBM to a container ship in Spain’s Port of Malaga. The fuel was supplied to Mediterranean Shipping Company’s container ship MSC Gabon from the LNG bunker vessel Avenir Aspiration.

By Konica Bhatt

Please get in touch with comments or additional info to news@engine.online

Contact our Experts

With 50+ traders in 12 offices around the world, our team is available 24/7 to support you in your energy procurement needs.