Australian refinery closures are evidence of a new wave of industry consolidation

Covid-19 has left refiners in a precarious position, but the impact of Australian closures is positive for product tankers.

The COVID 19 pandemic has resulted in one of the worst years refiners have ever faced. The catastrophic loss of nearly 10 million b/d of global oil demand has led to many refiners idling until economic conditions improve. That alongside a structural oversupply in refining capacity means the industry faces continued tough times for the next few years.

And with the continued addition of complex, integrated refining and petrochemical complexes in China and the Middle East, it is the marginal refiners that are less complex, located in Asia, Australasia and the Atlantic basin that will lose out. In addition to a recent spate of closures in Australia, the Marsden Point refinery in New Zealand has been operating at reduced rates and could be converted into an import terminal. Being the only refinery in the country, this leaves another isolated country in the region with a reliance on fuel imports. Closures in Europe also contribute to forecasts from the IEA that indicate 3.6 million b/d of refining capacity will shut between 2020 and 2026.

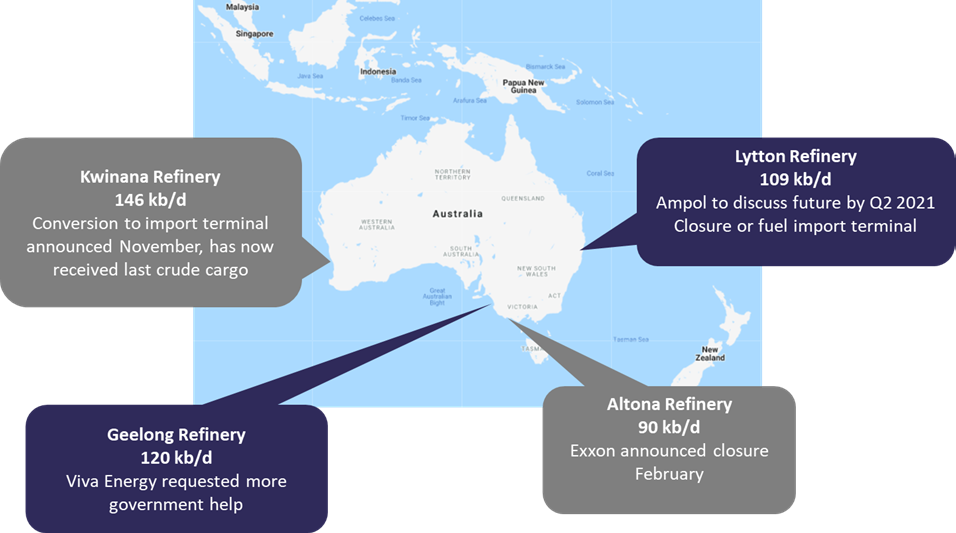

Australian closures leaves just two refineries

Last month ExxonMobil announced it would shut its 86,000 b/d Altona refinery in Australia. This followed news in November of BP closing and converting the Kwinana refinery in Western Australia into a fuel import terminal.

These two closures leave just two refineries in Australia. The Geelong refinery in Melbourne in the state of Victoria, which at 128,000 b/d will be the country’s largest remaining refinery. And then the Lytton refinery in Brisbane on the East coast with a capacity of 109,000 b/d.

Viva Energy, the company running the Geelong refinery, expect trading conditions to remain challenging this year and have accepted a governmental subsidy but has not ruled out closing Geelong. With the company planning to “resolve the refinery’s business for the long term this year”. Meanwhile, Ampol aim to discuss the future of the Lytton refinery by the end of Q2 2021. It remains to be seen whether these remaining two refineries will keep operating, although potentially the Australian government could be forced to step in with more generous subsidies to protect security of supply.

Why are Australian refiners facing closure?

These aren’t the first two refineries to close in Australia, and in fact follow a decade of closures which shows that in a globally integrated oil and refining market there is clear fundamental weakness in the economics of the Australian refineries.

One of the principal reasons is that the refineries are importing around 70% of their crude, and some of that from long distances. This high crude delivery cost will make them disadvantaged compared to US Gulf coast or Middle Eastern refiners that have a readily available supply of local cheap crude accessible via pipeline.

There is also the high cost of the crude slate, because as relatively simple refineries in Australia they are purchasing lighter, sweet crude which comes at a premium to heavier sour crudes. Despite the light-heavy differential reducing due to OPEC cuts, it is forecast to widen again, and so place simpler refiners at a disadvantage once again.

Furthermore, refineries will also be forced to spend money to upgrade their processing in the next few years to meet new tighter aromatic specifications in gasoline for the Australian market. In addition, operating expenses are also relatively high due to the lack of large economies of scale, and comparatively high labor costs.

Closures set to provide a boost for product tanker demand East of Suez

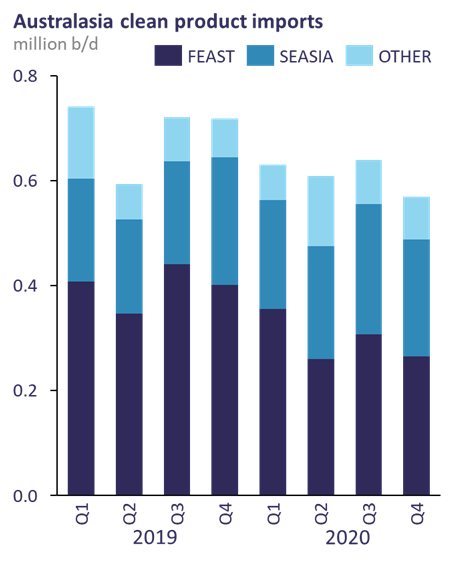

The big benefit to shipping will come from the need to increase fuel imports into the country. It is estimated that by the end of 2021 imports will increase by 300,000 b/d from 2020 levels, as demand returns to normal levels and the shortfall of supply from the refineries comes into effect.

This is a big positive for product tankers East of Suez. This product will come from the Middle East and India, and North Asia. Locations that have complex refineries where the economics are better. They will also receive product from the regional hub of Singapore. While trade from Singapore will be on MRs, journeys from the Middle East, and the Far East will attract LR2 and LR1 as well as MR tankers.

There is also a potential additional benefit for the LR2s in that with less aframax going into Western Australia, they might be able to take the Northwest shelf condensates on a valuable back-haul cargo which was previously an aframax trade.

We have calculated that for every 100,000 b/d of refining capacity lost in Australia, the market needs an additional 5 LR2 tanker equivalents. So, for the two refineries that are shutting down you would need around 12 additional LR2 equivalents, but obviously that is going to be spread between the MR, LR2 and LR1s.

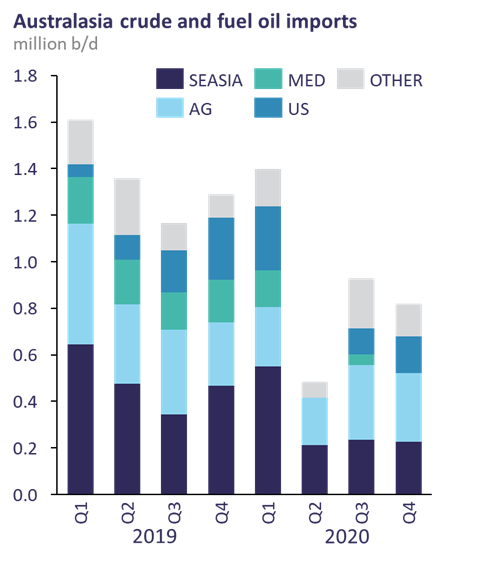

The positive shift for product tankers is balanced with the negatives on the crude side

The swing side is that things are looking less good for crude imports. Imports in 2020 were already 500,000 b/d down y-o-y due to lower utilization and they are not likely to see much of a recovery. The local source of barrels is Malaysia so this is a reasonably short-haul trade on an Aframax. But the big loss will be the long-distance routes of supply including the USA and North Africa. Losing these will be a blow to tonne-mile demand for the Aframax, and also Suezmax tankers.

Contact our Experts

With 50+ traders in 12 offices around the world, our team is available 24/7 to support you in your energy procurement needs.